Turning to the first page of the Da Vinci Code, I saw these words in bold italics: “FACT: all descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate.”

One of the most commercially successful novels of all time, Dan Brown’s mystery-thriller has been translated into 42 languages and has sold over 40 million copies worldwide. The novel has been marketed to society as one of the most controversial texts concerning art and religion of all time- despite the fact that it is a work of fiction.

In the story, a prominent curator of the Louvre is found murdered, and a respected professor of “religious symbology”, Robert Langdon, is called in to solve the mystery of the curator’s death. The narrative, though written in third person, is cast mainly from Robert Langdon’s perspective. Thus, the reader is capitulated into a highly controlled, believable theoretical space, and their ability to negotiate their own reading of the art is lessened. The intended hegemonic reading of this book is that the protagonist’s interpretation of art is the only credible or plausible one.

Robert Langdon is apparently a professor of “religious symbology” at Harvard University… But wait. A quick search reveals that Harvard offers no class by such a name! Ahem… anyway. In the book, Robert is described as a “veritable Harrison Ford in tweed” (Page 9). In fact, much like Indiana Jones, Robert is a talented academic who just so happens to be able to execute epic action sequences. It’s like his PhD enables him to dodge bullets at close range while simultaneously solving intricate cryptograms.

The only people who challenge Robert Langdon’s scholarly authority on Leonardo da Vinci’s art are religious fanatics. The most diabolical of them is Silas, an albino, and a monk of the conservative Catholic Group Opus Dei. He is a tragic character who suffered in poverty and exile until being welcomed into the extremist Catholic cult. His unwavering devotion to the cult, combined with his poor eyesight, signify blindness to the reader. This extends to his inability to see the hidden messages in Leonardo’s art. Just as Langdon’s taste classifies him as a connoisseur, Silas’ lack of regard for art classifies him as barbaric and completely ignorant to the world around him.

There seem to be two main theories in this book that engage with Leonardo’s art. The first is that the Mona Lisa is actually a self-portrait of Leonardo in drag. As cool as that would be, this idea has been widely refuted by scholars, as the painting has been attributed to a woman of the time. But this emphasizes how Brown has re-appropriated Leonardo, as both a historical person and an artist, to suit his thematic agenda. Referring to Leonardo as a “flamboyant homosexual” (page 45) is just plain derogatory. Regardless of the artist’s sexual orientation, this orientation-based stereotyping and lack of historical basis is pretty unfortunate.

There seem to be two main theories in this book that engage with Leonardo’s art. The first is that the Mona Lisa is actually a self-portrait of Leonardo in drag. As cool as that would be, this idea has been widely refuted by scholars, as the painting has been attributed to a woman of the time. But this emphasizes how Brown has re-appropriated Leonardo, as both a historical person and an artist, to suit his thematic agenda. Referring to Leonardo as a “flamboyant homosexual” (page 45) is just plain derogatory. Regardless of the artist’s sexual orientation, this orientation-based stereotyping and lack of historical basis is pretty unfortunate.

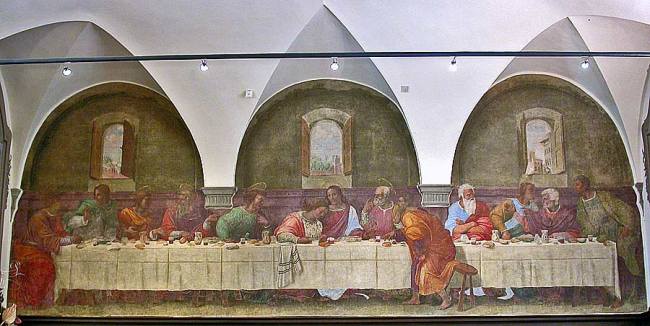

The second claim made is that the character to Jesus’ right in the Last Supper is not the Apostle John, but rather, Mary Magdalene. He claims that the lack of a chalice on the table and the feminine features of the character signify that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were actually married. Anyone with some knowledge of Renaissance art can tell you that a frequent way of depicting John was to show him as a beardless youth.

the Last Supper by Franciabigio (1514).

the Last Supper by Franciabigio (1514).

Also, why does the mass market book provide no images of the artwork? It interrupts the natural flow of the work of fiction to pause and search images online or in other books. The book is suspiciously set up so that we have to rely wholly on Brown’s “facts”.

One of the most abundant items of support for this book is that it is a splendid page-turner. And I agree. It reads like an action movie. There are 454 pages, and 101 chapters. That’s about 4.5 pages, on average, per chapter! I was ten chapters in before I finished my first cup of tea.

Stephen King once called this novel the “intellectual equivalent of Kraft Macaroni and Cheese”. That pretty much sums it up for me. It is almost universally digestible, is quick, convenient and enjoyable. It pre-supposes (maybe relies on?) the average reader having a limited grasp of art history. Too bad for me, I studied it for four years in university.

Perhaps this novel represents a good opportunity for us to begin to understand the value of a more active, negotiated reading.

And maybe it’s time we started eating more fettuccine alfredo.

Rating: 2.5/5 (It passes because it passes the time).